William Wilberforce’s campaign to end the slave trade entered its next phase in the spring of 1791. Parliament was back in session and yet more evidence was presented regarding the execrable trade in human beings. Wilberforce again spoke at length before the House of Commons but the measure for abolition was soundly defeated by a vote of 163 to 88. It was a bitter defeat that would become even more agonizing in years to come. Up to this point, the abolitionist movement had made considerable progress. Their efforts had made a significant impact upon British public opinion. But events across the English Channel would soon dramatically shift the landscape.

The French Revolution erupted in 1789, based upon the admirable ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The advancement of these noble concepts dovetailed nicely with the abolitionist movement in England. Abolitionists fervently endorsed the notion that all men have equal value before God and deserve freedom from oppression and tyranny. Are not all people – of any color – our brothers and sisters in the human race? Yet events in France soon turned dark and violent. The revolutionary forces turned their wrath upon the French clergy and nobility who had long exploited them. The situation descended into bloodshed. Sentiment was especially strong against the Catholic Church, which became a symbol for the old order of things. Catholic priests were hunted down and slaughtered. Many among the French aristocracy and clergy fled for their lives.

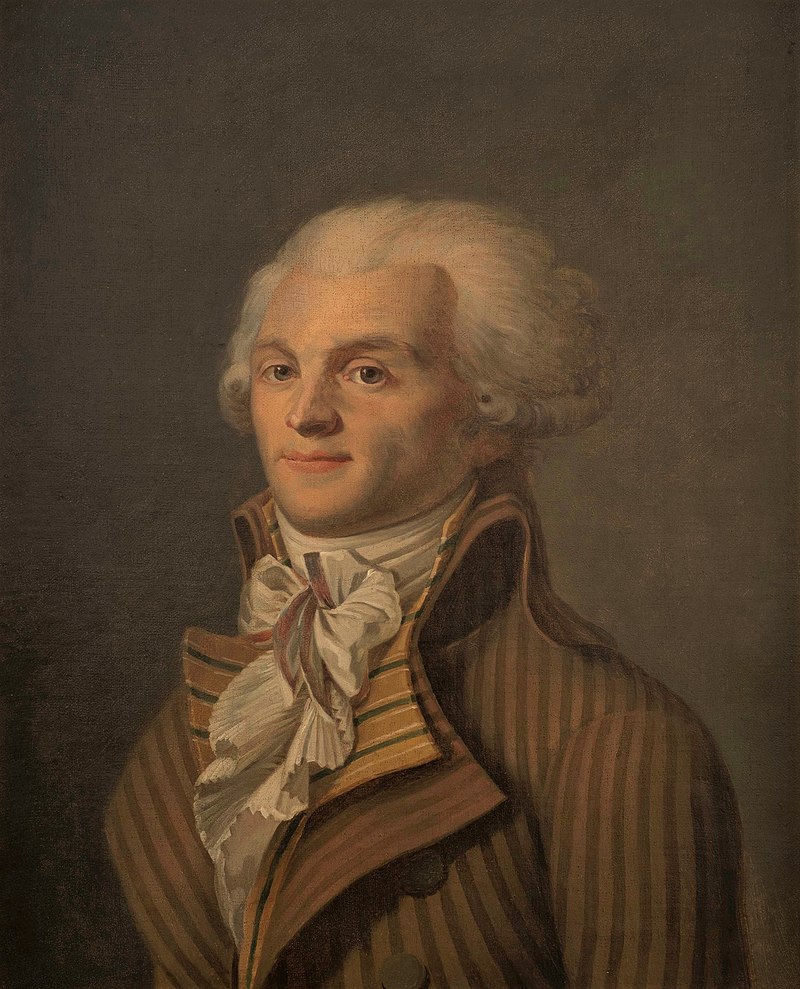

As time went on, more and more radical elements gained power. A lawyer named Maximilien Robespierre emerged as the leader of a group called the Jacobins. The Jacobins were not content merely having a greater voice in the political arena. They were determined to end the French monarchy itself. On August 10th, 1792, King Louis XVI was imprisoned and the National Convention declared that France was no longer a monarchy but a republic. Yet even this was not enough for Robespierre and his Jacobins. They believed that the revolution could not ultimately succeed while the king still lived. So in early 1793, Louis XVI was sent to the guillotine. The king’s wife, Marie Antoinette, would soon meet the same fate.

The death of the king failed to stabilize the revolution. In fact, just the opposite occurred. France plunged into an unmitigated bloodbath. The radical Jacobins did not hesitate to behead anyone who they thought might stand in their way. During the infamous “Reign of Terror”, Robespierre and his allies killed over 40,000 people. The guillotine became known as “the national razor.” And it was no longer just the aristocrats and clergy who feared for their lives. Even those who had at first supported the revolution were quickly deprived of their heads if they dared to oppose the radical agenda.

Needless to say, those in Britain watched in horror as the French Revolution devolved into bloody carnage. The lofty ideals of liberty and equality had been replaced by hatred and paranoia. Tragically, the events in France badly crippled the abolitionist movement in Great Britain. No longer could the noble concepts of human equality and dignity be advanced without conjuring up dark visions of headless bodies and social anarchy.

Thus, when William Wilberforce again brought forth his motion for abolition in 1792, the pro-slavery forces had the advantage. The debate raged all through the night. But, fully aware of what was transpiring in France, many in Parliament had lost their taste for complete abolition. Instead, a proposal for the gradual elimination of the slave trade gained support. This proposal played right into the hands of the slaver traders, for they realized that the ground was shifting in their favor. The longer they could delay, the more likely they could scuttle abolition altogether. The motion for gradual abolition passed but the slave interests were correct in their assessment. By 1793, the French monarch was sent to the guillotine and the French Republic declared war on Great Britain. Abolition had now been pushed, not just to the back burner, but off the stove top altogether. The House of Commons refused even to confirm its earlier vote on gradual abolition.

To many people in England at this moment, Wilberforce’s continued campaign against the slave trade now seemed impractical at best and downright unpatriotic at worst. Why should Great Britain be concerned about the slave trade when France was then exporting dangerous revolutionary ideas that threatened to unravel English society itself? Moreover, would not the end of the British slave trade simply push this lucrative business into the laps of the French, thereby filling the French war chest against the British nation? The British war hero Lord Horatio Nelson was one of this opinion. “I was bred in the good old school and taught to appreciate the value of our West Indian possessions…their just rights shall [not] be infringed, while I have an arm to fight in their defense or a tongue to launch my voice against the damnable doctrine of Wilberforce.”

Already drunk with blood and power, Robespierre eventually became completely unhinged. He even accused his fellow radicals of failing to support the revolution. They responded by sending Robespierre himself to the guillotine in 1796. After the execution of Robespierre, the threat of French-style revolution waned in Great Britain. This provided a window of opportunity for William Wilberforce and the abolitionists. Again bringing forward his cherished motion for abolition in 1796, Wilberforce was on the cusp of victory. Yet it was not to be. The vote was excruciatingly close, defeated by the narrow margin of 74-70. This result was even more bitter considering that the pro-slavery forces had shrewdly given free opera tickets to supporters of abolition in Parliament. Wilberforce was nearly heartbroken that a handful of his colleagues had allowed the slave trade to endure in exchange for a night of entertainment.

As the French Revolution dragged on, the people of France had become exhausted by the turmoil and violence. Most everyone longed to restore some semblance of stability to French society. Some even yearned for the restoration of the monarchy. Well, it turns out that such a strong, central figure would soon arrive on the scene. Napoleon Bonaparte had first achieved notoriety for his military prowess in 1796 when he led the French forces to a series of shocking triumphs over the armies of Austria. He quickly became a national hero and capitalized on his popularity by staging a coup in 1799, essentially becoming a dictator. Yet even dictatorial powers could not satiate Napoleon’s boundless ambitions. In 1804 he (literally) crowned himself Napoleon I – emperor of France.

In 1805, Napoleon developed plans to invade France’s perennial rival Great Britain. He gathered a powerful French invasion force along the coast of the English Channel. Great Britain rightly feared Napoleon’s military superiority on land. Fortunately, the British Navy still controlled the seas. On October 21st, 1805, the British naval forces – led by Admiral Lord Nelson – achieved a devastating victory over a combined French and Spanish fleet off the Spanish coast near Cape Trafalgar. Although Lord Nelson was killed during this engagement, the triumph ensured British naval supremacy for decades to come.

Although the Napoleonic Wars would continue to rage across continental Europe, the battle of Trafalgar ended the threat of French invasion. Heretofore, William Pitt and the British Parliament had been understandably preoccupied by the danger posed by Napoleon. During these years, the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade had again been pushed out of the national consciousness. But now that the British Isles were safe from invaders, Wilberforce and his allies were able to advance the cause of abolition with renewed vigor.

Wilberforce’s close friend William Pitt died in early 1806, worn out by the heavy responsibilities of leadership during the crisis years of the French Revolution and subsequent Napoleonic wars. Pitt had always been a friend of abolition. Thankfully, his successor to the office of prime minister, William Grenville, was also a fervent advocate for outlawing the slave trade.

In 1807, all the long years of toil and discouragement gave way. There was a renewed surge of support for Wilberforce and abolition. Grenville shifted tactics by advancing abolition first in the House of Lords where it had always faced its fiercest opposition. Although not known as a fine orator, Grenville at this moment rose to the occasion. He spoke powerfully on behalf of abolition, giving full credit to the tireless exertions of William Wilberforce, who watched from the gallery. Grenville memorably advanced abolition as “a measure which will diffuse happiness among millions now in existence, and for which [Wilberforce’s] memory will be blessed by millions yet unborn.” The House of Lords approved the bill by a staggering margin of 100-36. Only one final hurdle remained. The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act now went before the House of Commons, where William Wilberforce awaited.